We often forget how different and in some ways complicated it is to be punk and play punk in places in the world other than Europe and the USA. Often we don’t even think that punk (in its various forms) can be, for many “minorities” a fundamental means to make their voices heard, rediscover and spread their cultures and impose their claims and struggles at the center of the discourse and within the broader movements of anti-capitalist struggle and against the state. For many punks belonging to indigenous cultures and First Nations, playing this genre means first of all imposing a discourse of indigenous resistance and decolonization paths, making punk really a threat and not just empty slogans shouted into a microphone. About this and much more I was lucky to talk with two comrades from Native Punk, an indigenous and anarchic collective based in Guatemala (and linked to the d-beat/crust band Mother Earth) creators of Tribal Punk podcast and active in the promotion of a network of indigenous and native bands within the punk scene of the American continent. Make indigenous resistance a threat again!

Hi! I want to start this interview by talking about your Tribal Punk/Native Punk project. How did this project come about and what goals did you set for yourselves?

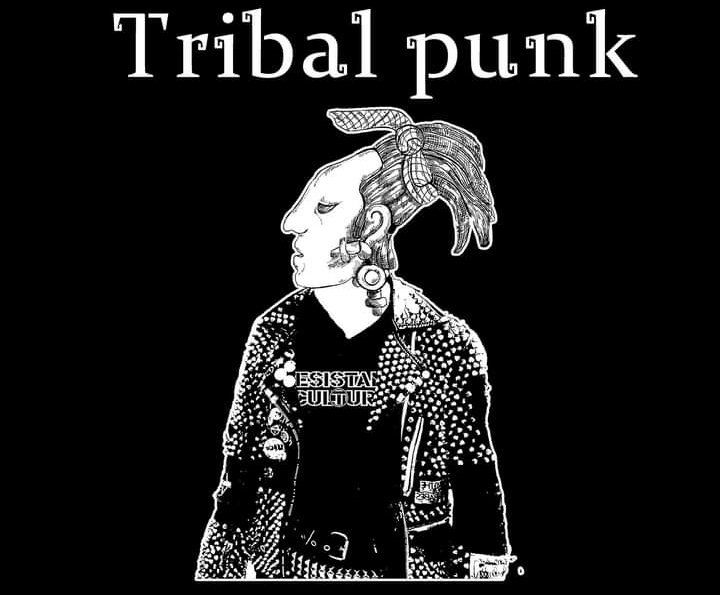

KT: I think the project started out of personal interests. As indigenous people we always wonder about the presence of other indigenous people in punk scene in other countries, mainly we wondered if there were bands that claimed the ethnic issue within punk throughout the American continent. Actually, at first, we just thought it was interesting to find or know about a band like that, but beyond simple interest we had no goal. I remember that the first band we heard, that everyone has heard, was Resistant Culture, but I remember that our interest increased significantly, and the first steps as a collective began, when we heard Pool, a band from Mérida, MX; they sang in Mayan-Yucatecan, and they played a kind of hardcore punk/skrams. At least, I remember that that was a turning point for me, meeting that band, because it was the kind of music we were listening to a lot back then, and it was like fast youth angry hardcore. From that we started talking about this project, the first idea was to just make a compilation on Bandcamp, the idea was simply to get bands from Latin America and compile them, and nothing more. The idea arose from other compilations, for example, I had seen a compilation made in Brazil by an Argentine girl of bands with a presence of women in South America, I don’t remember the name of the compilation. Anyway, we were looking for bands, but we found very few, and eventually we gave up. That’s how after years of googling and finding very little, the idea of making an archive of this type of bands came up.

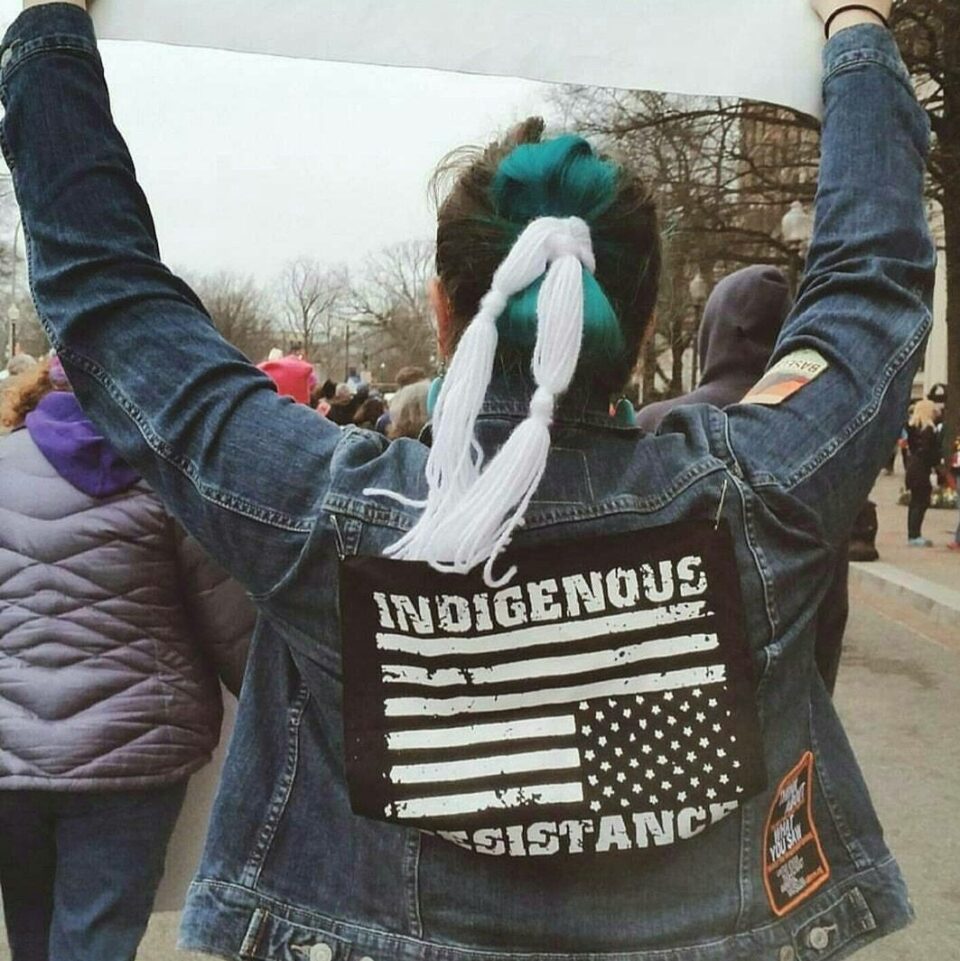

SI: We had this curiosity about the music made by Native People, we had many ideas, we talked about fanzines, compilations, collecting all these bands, because we always searched and couldn’t find them. We were curious if there were more people asking these same questions, who wanted to discover this whole issue of punk of the indigenous peoples. From that we began to collect and at first, they were just for us, passing bands among ourselves. Later, that motivated us to start documenting through an Instagram account, uploading the album covers and some basic information about the bands. That gave way to the creation of the podcast, which was some time later. That’s how this project started. And about the goals, one of the goals was to give visibility to indigenous punk bands, because the vindication of ethnic identity is a very important political act, especially in the punk scene of the American continent, that does not escape from widespread racism and the colonization of these States. In the Latin American punk scenes, for example, not much importance is given to these bands, nor to the ethnic self-identification of the people in the scene. Thus, we seek to make visible the bands, the indigenous punk scenes and the indigenous languages in which many people communicate and sing. All of that by creating the band archive, compiled material, and everything that punks do, like fanzines and stuff…

KT: I wanted to add another thing, about what you were saying, and that is that we also seek to encourage more indigenous people, mainly throughout Latin America. For example, they have told us, people with whom we have spoken from other territories of Latin America, that there has always been indigenous participation in the punk scenes, there are always indigenous people who frequent the shows, or people who make bands, old punks, young punks, but rarely have decolonial themes and indigenous themes been taken as a central theme in the discourse of the bands. The objective is to make visible and encourage indigenous people to make punk and punk bands with decolonial discourses and in languages other than Spanish, English or Portuguese, which are the largest languages spoken on the continent.

SI: Even in countries like this (Guatemala) where the indigenous population is close to 50%, it is curious that more music is not made in the original languages, but in Spanish and English.

Where are you originally from? What indigenous nation, people and native culture do the people behind Tribal Punk belong to?

At the moment we are only two people, who met in the territory occupied by the Guatemalan State, Ka’i’ Toj (KT) from the Mayan-Kaqchikel people and Saq Imox (SI) from the Mayan-K’iche’ people.

Can we consider Tribal Punk as a real collective engaged not only in the promotion of indigenous bands, but also in the political instances of different indigenous and native peoples such as anti-colonial struggles, decolonization processes and in general the fight against racism and cultural discrimination suffered even today?

KT: The collective does go beyond the promotion of bands, because we have had other projects, and we have other projects as part of the goals, apart from encouraging, collecting and archiving these bands we are also thinking of creating other types of materials such as fanzines, in which these issues are discussed more clearly, mainly racism. I would say that these are the most immediate problems that interest us, related to anti-colonial and decolonial issues, and that affect us the most in Guatemala and throughout the continent. For example, I don’t know exactly how old punk is in Guatemala, but in all these years, even though there have been indigenous people playing and “leading” bands, has never been openly talked about indigenous issues, it has never been discussed, no attempt has ever been made to present a decolonial punk, much less in indigenous languages (in Guatemala there are 24 indigenous languages). And apart from countercultural production, which is music, fanzines, etc., we are also creating a collective based on affinity networks, of indigenous anarchist youth, I would say, in the long term, but we are working on it, trying to contact more indigenous people from the Guatemalan scene interested in participating, and from other scenes in other countries with whom we have contact from north to south.

SI: Through the podcast we have talked to a lot of people who were very interested in the subject, and each one of these people, each one of us, have alternative projects, not exactly punk, but in the strengthening of indigenous identity and decolonial struggle. And among all of us we want to mix our ideas and our projects. For example, I have a project for a school for children, youth and adults in which we seek to disseminate indigenous and Mayan art, through workshops and classes about the construction of native Mayan instruments, performance, appreciation, painting and epigraphy, which is the study of the ancient Mayan form of writing.

KT: In general terms, we seek to promote decolonial indigenous values, as well as the use of indigenous languages in all spaces, we seek language justice, we seek to have material produced in native languages.

What is the history of the indigenous and tribal punk movement? When did the first relationships between the punk scene and indigenous cultures and peoples arise?

KT: I don’t know if we are talking in global terms or in local terms about ourselves, about our communities, our peoples, within the Guatemalan State, but I would say that indigenous participation —and that can be said by anyone who knows the scene minimally in any Latin American country— and the relationship between the indigenous population and punk has always been very close. In Guatemala we have the case of one of the first known punk bands (Warning), it was led by a boy from an indigenous village, although they never sang in any indigenous language, and honestly, I don’t know if they claimed the ethnic issue (I think not). And I think that something similar happens in all Latin American countries, there are always indigenous people involved in the punk movement, especially in countries with a significant indigenous population such as Guatemala, Mexico, Brazil, Peru, Colombia, Ecuador, Chile, etc. I think that the relationship between punk and indigenous peoples in Latin America is almost as old as punk in this region, from the involvement of urban indigenous people who were entering the youth movement, like other people at the time. And I don’t think there is a more organized movement like an indigenous-punk movement (not yet), but there have always been indigenous people within the Guatemalan scene, which has also happened in other countries. In general, I think it has also happened throughout the continent, including northern North America (USA and Canada), for example, Resistant Culture has a Demo from 1986 or 1987, I’m not sure, when they were not yet called Resistant Culture but Resistant Militia, a band that emerged alongside the evolution of punk, in the 80s. I think that punk by its very nature has presented these characteristics in the Americas, and it has been a fertile field for this to happen, with all the bad and shit that punk has.

Why do you think many indigenous individuals use punk, hardcore, and related genres to make their voices heard, to impose their own discourse and history that colonialism has attempted to erase forever, and to advance instances of resistance, struggle, and attack on a world in which the West/Europe has tried to stifle every other indigenous and native culture?

SI: I think that, due to the very nature of these genres, which are adapting to the needs of each generation, and what we were talking about above, one of the first punk bands in Guatemala was “led” by a person from an indigenous village, although he did not talk about these issues, because they were coming out of the time of the war in Guatemala, then I think it was not seen as necessary as it is now. Now we use music, because we appropriate punk, all the characteristics of punk, of being dissatisfied with colonialism, with the way the West has tried to suppress our cultures, and we see punk as a platform where we can shout it out and say that we don’t like colonialism and that we are proud of our ethnic identity, of our native peoples.

From what I could see on your Instagram profile and by following your podcasts you focus on indigenous punk bands from the Americas. What do you think are the most interesting bands, movements, and situations currently within the indigenous, tribal, and native hardcore punk scene?

SI: I really like the indigenous punk scene in North America (specially in USA and Canada), because it is a little more diverse in terms of kind of music, there is a youth crew band (With War), in which a girl sings, who touches all these indigenous issues, and they are straight edge. It seems too good to me because here in Latin America we are more used to these topics being addressed by crust punk and anarchopunk bands. Most tribal punk, native punk and indigenous punk bands are bands related to those genres. Indigenous punk scene in the US and Canada is more diverse, with bands of various genres; well, and hip-hop, which we also like, but I think it’s more common to find indigenous hip-hop throughout the Americas. But I perceive that indigenous punk is a little more varied there, that’s how I see it from here, from what it seems on the Internet, I really don’t know, but it catches my attention.

KT: And although we are enthusiasts of crust punk, d-beat and black metal, there is a band that I really liked called Indian Giver, which is a kind of hardcore/post-hardcore. On their Instagram they put that they are from various indigenous peoples of the north (Ojibway, Mohawk and Mi’kmaq). In other hand, I also find the punk scene in Mexico very interesting, and especially in the south of Mexico, where there is a lot of indigenous movement within punk. There is a very interesting documentary called MacehualoPunks (2019), it is about the indigenous punk scene in a small town in Veracruz, Mexico.

A question you may not want to answer. As the individuality behind the Tribal Punk project, are you active in any avenues of struggle? If so which ones?

Apart from what has already been mentioned, we are involved in various instances at the community level, following the struggle guidelines of our specific communities. As we mentioned at the beginning, we belong to two different indigenous peoples and communities, and at the moment we act from our own community spaces.

What do you think are the most important problems, difficulties and paths of struggle that the different indigenous communities (based on different histories, cultures and socio-political-geophysical contexts) in the American continent are facing today?

KT: This is a very difficult question to answer, because the indigenous peoples in the American continent (Abya Yala), from the North Pole to the South Pole, live under a colonial system, a caste society and a systematized racism that has been around for centuries; trying to assimilate us and/or erase us from the maps. All the States of the continent have had racist policies, in all the States of the continent there were genocides and attempted genocides against indigenous peoples, all the States of the continent were built on the idea of whiteness, there is a lot of evidence that confirms it. This makes indigenous peoples and people with an ethnic and class consciousness face a dark panorama full of struggle.

The central problem is the extractive capitalism. Just to mention the ones that come to mind first, as examples: (a) the problems faced by the indigenous peoples of the Amazon, especially on the side of the Brazilian State, in the face of the fascist and neoliberal advance of agribusiness and mining, encouraged by the current government of that country, and the uncertainties that all this generates in the control of their own territories; (b) mining and large monoculture farming (banana, sugar cane and palm oil) that violently extend over indigenous territories in Guatemala, especially in the north, in Mayan-Q’eqchi’ territory; (c) the militarization and criminalization of the fight of Mapuche territory, in the south of the continent (in the States of Argentina and Chile, especially in the latter), historically warrior people, who continue to fight for their territory against agribusiness; (d) or the construction of gas pipelines in indigenous territories occupied by the Canadian State. Finally, I believe that one of the most important paths of struggle of the indigenous peoples in the Americas, which have an ethnic and class dimension at the same time, is the indigenous peasant struggle, that is one of the fronts to which I bet, and in which the population in general can contribute in a practical way, by entering the circuit of consumption of products of peasant and indigenous origin, especially in Latin America.

As a lover of extreme metal, I have realized more and more often in recent years that there is a strange link between indigenous metal bands (or allegedly so) and environments close to the far right, Nazi-fascism and ideas of racial supremacy. I am thinking especially of bands affiliated to O.N.S.P. (Organizacion Nacional Socialista Pagana) a Mexican political collective of extreme right, bands that take the history of Aztec culture declining it in a supremacist, racist and fascist vision. How do you explain such a phenomenon? How is it possible that the history of indigenous cultures can wink at political positions of colonial oppression, race supremacy and similar scum?

SI: I can also consider myself a lover of extreme metal. But perhaps, we saw in the punk platform a possibility to express all this, because we realized that within metal, everything is very ambiguous, and everything changes direction. While in punk we have clearer ideas, clearer space, a space in which we trust, in which we feel freer to express our ideas, without being confused with ideas of nationalism, for example, ideas that are very contradictory. As the question says, all these ideas are colonial oppressions, something with which we do not agree, and we believe is something very illogical. We really do not agree and do not accept in the least this type of ideas, racism, suprematism, but we accept that we are in multicultural territories, in which we and everyone have the right to ethnic and cultural identity.

KT: I think that in metal there is no political clarity, or at least it is not generalized, there is no defined political ideology, it never existed, because of the way it emerged, that it had little to do with political movements and was just people wanting to be “rebellious”. Then they started talking about things that seemed rebellious depending on the time and place, which was what happened with black metal in Norway in the 90s. From then on everything was a mixture without a very defined ideological form, because a lot of elements are mixed, in the case of Latin America, copying other scenes, those of Europe and the US, mixing elements without much notion of what is being talked about. For example, I wonder about these O.N.S.P. bands, which have truly indigenous members, and how many, the examples of these gangs that we see in Guatemala are made up of non-indigenous people.

SI: I think that many of these bands fall into the folklorization of the country, it’s a cheap nationalism. It’s like being proud of your country, and “your culture” and dress up as “ancient warriors”.

KT: Finally, it is not different from the nationalist propaganda for tourists that the States do, in Latin America especially. For example, the Guatemala State and the Mexican State try to sell their country as an attractive commercial product for tourists. This is also part of the State policies of the construction of a national narrative (and the founding myth of the State and “nation”), where the State is only interested in the aesthetics of the native peoples and not in the very existence of these peoples, and separates “good indians” (the civilized westernized nationalist) from “bad Indians”, those who are truly rebellious, the anti-colonials.

We’ve come to the end of the interview, so I thought we’d say goodbye with one last question: what is the future of indigenous punk and what goals do you have for it in the short and long term?

SI: One of the things that would be cool is to hear more bands sing in their native languages. That they also use their native instruments, talk about the reality of the native people of each territory from which the bands arise. What excites me the most, and a lot, is being able to listen to more bands in their languages in a couple of years.

KT: To say goodbye, I wanted to thank Disastro Sonoro for the interview. We are looking for these spaces to make noise and start discussions on the indigenous issue in the Americas. Any type of discussion is welcome, you can contact us at IG: tribal punk